“Wild geese, wild geese, fly in line, show me the way home”

From Sato-gokoro, a Japanese Lullaby

We have entered the micro-season of “Geese Fly North”. This is the second micro-season of the mini-season of Clear and Bright.

Each mini-season contains three micro-seasons. The micro-seasons contained within Clear and Bright are:

- The Swallows Arrive (April 04 – April 08)

- Geese Fly North (April 09 – April 13)

- The First Rainbow Appears (April 14 – April 20)

These seasons were established in 1685 by Japanese astronomer Shibuka Shunkai and are specific to Japan. However, just because the calendar focuses on Japan doesn’t mean it doesn’t apply to others. No matter where you live you can use these seasons as a starting point for your personal exploration of the world around you.

In this micro-season, we notice the spring migration of geese. For those in the northern regions, it might mean that the geese are returning from their winter residence. For those in the southern areas, it might mean that the geese are leaving.

What is bird migration?

At its most basic form, bird migration describes the seasonal movement of a bird species. Many factors contribute to bird migration including the availability of food and breeding grounds, genetics, the length of daylight, and temperature changes.

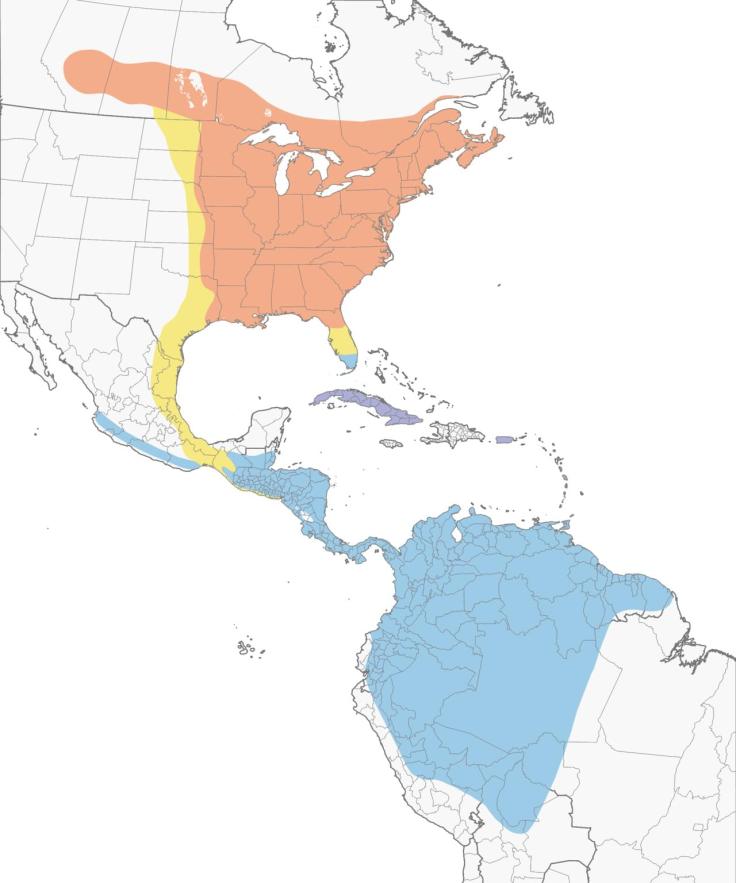

The distances birds migrate can also vary greatly. Some birds participate in short-range migration, which can be as little as moving down a mountain to about 100 miles. While others participate in mid-range or long-range migration. Mid-range migration is usually a few hundred miles, while long-range can be several hundred miles. An example of long-ranged migration is the broad-winged hawk which migrates from New England to South America.

But Where is Home?

Did you ever wonder if spring migration was a process of birds leaving from, or returning to their primary home? Well, it turns out that ornithologists had the same question that led to a study on the evolution of bird migration.

Scientists posed two hypotheses for this study. One hypothesis suggested that a bird’s home territory was in the north and they migrated south for the winter. The other was that the bird’s home territory was in the south and they migrated north for the summer. These two groups were called the “Northern Home” and “Southern Home” groups.(2)

To figure out whether the birds were originally southern, or if they were originally northern birds, the scientists looked deep into their evolutionary past. Benjamin Winger, a professor at the University of Michigan, analyzed the lineage of 800 migratory songbirds. He did this by developing “a model that used the evolutionary tree for these many species to predict the ancestry of their seasonal migrations. Their model reconstructed changes in the breeding and nonbreeding distribution of these birds throughout their evolutionary history, which provided a basis for estimating how the birds’ migration patterns had evolved over time.”(2)

The results of the research indicated three things. First, it was more common for long-distance migrators to shift towards more southern and tropic regions rather than the other way around. Second, some birds who are permanent residents of the tropic regions are descendants of migratory birds that lost their migratory traits. And third, it was more common for migratory birds to claim a “northern home” than a “southern home”.

The Impact of Climate on Migratory Birds

Bird migration patterns will evolve with climate change and its impact on vital resources. However, as the rate of climate change increases, the birds are struggling to keep up with the shifts.

As seasonal temperature patterns change, plants and insects are beginning to emerge earlier in the year. This becomes a challenge for migratory birds who depend on insects to feed their hatchlings. An example of this comes from a recent study of the European Pied Flycatcher.(2) A study showed that the insects a Flycatcher uses to feed their young now emerged before the Flycatcher arrived in northern Europe. This has led to a mismatch in life cycles for both the insects and the birds.

Luckily, researchers have noticed that young Flycatchers have started making micro-changes in their behavior to arrive earlier at their breeding ground. Although this is a bit of good news for the European Flycatcher’s survival, the fact that they need to make these micro-shifts to survive is very concerning.

The Impact of Humans on Migratory Birds

The story of Canada Goose provides a great illustration of the potential impact that humans can have on migratory birds.

In the early 1900s, the Canada Goose was almost hunted to extinction. Then, around 1950, with the support from governmental and conservation agencies, these birds made a triumphant comeback. Now an estimated 7 million geese are living in North America.(3)

The Canada Goose population of North America is divided into two categories: migratory birds and resident birds. The migratory birds are the ones following migratory paths between North America and Central and South America. The resident birds are the ones that are living in the suburbs, parks, and nature reserves. The resident birds are the ones with the largest population growth and the ones that are most challenging for humans.(4)

In a 2020 article for National Geographic, Brian Handwerk reported that “in the late 1970s, only 10 percent of the geese that lived along the Atlantic and Mississippi flyways . . . were residents. Today, they make up more than 60 percent.”(5) In that same article, Handwerk talks with Cornell University ecologist Paul Curtis who explains that humans have “created ideal habitats for these birds.”(5) It seems that the goose is thriving because the suburban areas provide easy access to food and protection from natural predators.

Although there are some reports that the increased residential goose population stresses the local nature preserves and wetlands (4), most of the challenges come from the goose’s contact with humans.

Geese cause aesthetic problems because they eat grass and damage lawns and golf courses. They also create environmental hazards with their waste. Environmental hazards include water contamination and high coliform levels.

Then, there are potential safety hazards. Geese can be aggressive towards humans during mating season. Geese have also been known to interfere with air travel. The Federal Aviation Administration estimates “there are 240 goose-aircraft collisions each year nationwide”.(4) The potential of a goose-aircraft collision is a big concern because the consequences can be tragic.

How to Handle the Residental Goose Population?

Like many complex situations, the response to the growing number of geese in residential areas is varied. The geese are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and this restricts individuals and governments from using lethal controls without permits. However, as Pat Leonard reports, the common techniques to manage residential geese include, “preventing public feeding, altering the habitat to reduce its attractiveness to geese, hazing to scare geese away, using chemical repellents, hampering reproduction, and lethally removing the geese.”(4)

However, not all communities see the residential geese as a nuisance. Their increased population will continue to create opportunities for conflict until a balance can be found between their needs and our own.

Seasonal Haiku

As I like to do with all these posts, I want to close with a few poems that fit in with the season. Today’s selection comes from the early haiku masters: Kobayashi Issa, Matsuo Bashō, Yosa Buson, and Masaoka Shiki

To start, Issa wrote this haiku about the migrating geese.

from this day forth, geese, you are Japanese. now enjoy your rest. -Issa

In Japan, there are nine species of geese including the Cackling Goose, the Brant, and the White-fronted Goose. The White-fronted Goose, which arrives in Japan in the winter, makes up 90% of the geese on the island.(6)

Basho’s haiku is a bit different as it focuses on the voice of the goose and not the flight.

the sea darkening – the voices of the wild geese crying, whirling, white. -Basho

Buson then contributes:

a line of wild geese; above the foothills, the moon as seal -Buson

And Shiki finally adds:

railroad tracks; a flight of wild geese close above them in the moonlit night -Shiki

If you are interested in reading more about wild geese, haiku, and haiga, take a look at issue 16:2 of HaigaOnline.com: The Wild Geese Issue.

Mary Oliver and Wendel Berry have also written some great goose-related poems. You can find both poems here.

Let’s Spread the Joy of Haiku!

Buy a haiku book for the Woodbury Community Library (Woodbury, VT) and help them spread the joy of haiku! Follow this link to see the wish list and how you can help.

Thank you for your support!

You can also support our work by donating at “Buy Me a Coffee” or shopping at our bookstore.

Resources:

- AllAboutBirds: The Basics Of Bird Migration

- “The Evolution of Bird Migration”: AllAboutBirds.org

- “Canada Geese: frequently asked questions” Canada.ca

- Pat Leonard: “Where Did All Those Canada Geese In Town Come From?”: AllAboutBirds.org

- Brian Handwerk:” Do Canada geese still fly south for winter? Yes, but it’s complicated”: National Geographic

- Ishi Hiroyuki; “The Flight of the Wild Geese”: Nippon.com

Many of the goose-related haiku were found on the World Kigo Database. Check this site out to learn more about kigos and haiku.

Want to support our work? Visit the Naturalist Weekly bookstore and browse our curated lists of books on poetry and haiku. Or pick up a gift card that can be used throughout the store. Naturalist Weekly accepts donations for coffee and journals. Your support will keep both the coffee and content flowing.

Yay! The Canadian Goose! (lol!) I like them. I like them stopping traffic as they decide to walk across the road. They are lovely with their babies. Nice post as always, thank you!

Hi Adele, In researching this post I notice several photos of geese walking in front of school buses! Have you ever had that experience?

Yes, Mark! As a matter of fact, I had! Thank you for asking! (lol!)

Definitely residents locally. I don’t mind them. There are a couple of handicapped geese living out their lives at the local nature center.

In the research it definitely seemed like some people enjoy have them around, while other did not. Good to hear that you have a nature center that welcomes them. Thanks for sharing!

Very interesting to read, thanks for sharing this info

I am glad that you enjoyed this one. Thanks for stopping by and commenting!

Thanks for your work on bird migration. Fascinating subject– where is “home” for migrating birds, here, where they might stay a few months for the nesting season, or there, where they might survive for the balance of a year, etc. A lot to learn & think about!

Hi Walt, I agree that the idea of “home” for migrating birds was fascinating. I always just assumed north was home, but I realize that was probably just because I live in the north. I glad somebody actually tried to figure it out. Thanks for the comment!

Yes, in Virginia, they are resident birds. Basically, the Fish and Game people have posted signs not to feed them ever. But people still do. They leave their poop all over the school yards. So there is that.

Humans also increased the range of the Northern Cardinals with bird feeders.

I remember you mentioning that Geese were year round residents where you live. I can only guess the mess they make! Thanks for adding to the story!

Very lovely. 🙂

Hi Sara, I am glad that you enjoyed this. Thanks for the comment and visit!

fascinating and love the haikus

I am glad that you enjoyed this one! I agree that the haikus are great. Thanks for the comment! Talk soon,

There’s much good info here, Mark, but I confess to mostly being glad you didn’t write “Canadian Goose.” Not that I thought you would, but still. 🙂

Hi Tracy, I will have to admit that I often say Canadian goose in conversation! It is a hard habit to break and sometimes it just sounds better to my ears. But thanks for noticing! Thank you!

It totally makes sense since other birds are American Crow or American Kestrel. I don’t know why it’s Canada Goose.

Here is what I found on the outdoorsforum.com. . “It’s important to know that the Canada Goose was actually named after John Canada, not the country Canada.” There is a story here!

Wow. Okay, now that makes sense and also YES to a story here! Thank you for sharing that tidbit, Mark. 🙂

On the farm (yay, another farm story!), we had migrating Canadian geese every year. They’d settle in our wheat field (which surrounded a pond) and hang out for a few days. Their calls were seasonal harbingers and I always found them fascinating and beautiful creatures. That wheat field was also stomping grounds for a local herd of elk (sometimes number more than 80) and deer, and occasionally I’d see foxes and coyotes slinking about. I wonder if there are any haiku about wheat fields and animals that frequent them? Anyway, I love this article, and the haiku were delightful and always welcome. Nice work, Mark! 🙂

I am not sure about haiku about wheat fields. I wonder if Kerouac would have any. Thanks for sharing another farm story! I enjoy them. Thanks again and talk soon!

Fascinating, especially the Japanese names of the seasons and the concept of home. But still hard to love Canada geese that poop all over one’s grass and sand.:-)

Hi Sharon, Yes! I hear you. You must live in a place with resident geese!

Mark,

Informative post; thanks for pointing it out to me via the link. Now, I have learned more about migration and the coming and going of birds. I guess because I live in an area which is a flyway, we have both northern and southern birds.

We have Canada geese here in Ohio. We joke that they are illegal aliens (without green cards or I68s), but they are technically citizens since many were born here. They can’t go back to Canada even if they wanted to because of the lack of the right documents.

~Nan